Member Profile: Michael Peres

What is, or was your primary line of work?

I recently retired as professor of biomedical photographic communications at Rochester Institute of Technology. I joined the faculty September 1986. Before coming to RIT, I worked as a medical photographer in Charleston, West Virginia. I moved to become the coordinator of photographic services and education at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan.

At RIT, I teach many different courses including Media Foundations, Applications of Science Photography, Photomacrography, Photomicrography, Surgical Photography, Panoramic Photography, Capstone classes, and Advanced Biomedical Photography. I have served in variety of leadership positions in the school including the Program Director of Biomedical Photographic Communications and the Associate Director of School of Photographic Arts and Sciences. I am currently the graduate director for the Media Arts and Technology program.

What got you inspired to be a photographer/educator? Tell us about your career path.

In the early 1970s I had volunteered to be the sports editor for the high school yearbook. By happen chance, I watched the photographer develop film in his home darkroom, which was my first experience with photography and I was hooked. In 1973, I bought a Minolta SRT 101 camera with two lenses and shot miles of Kodak Tri-X film beginning what has been a fifty-year adventure.

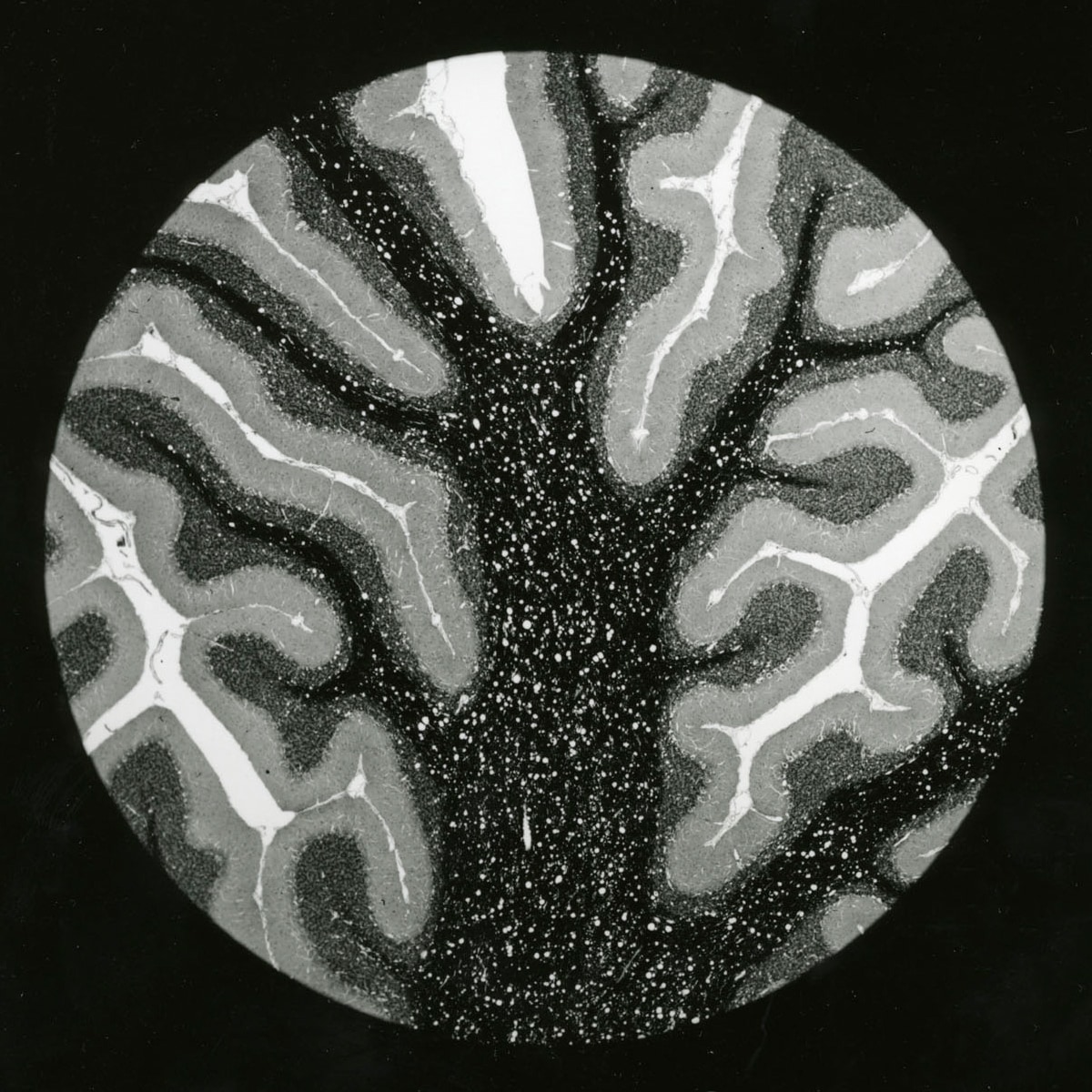

This photograph features the nerve pathways in a prepared slide of human cerebellum. The picture was part of a series of circular photomicrographs for an exhibition. The image magnification at capture was x30. © Michael Peres

This photograph features the nerve pathways in a prepared slide of human cerebellum. The picture was part of a series of circular photomicrographs for an exhibition. The image magnification at capture was x30. © Michael PeresI went to Bradley University as a biology major, but continued to work with photography. I was hired for a number of jobs that all involved photography. I worked as the student photographer for the university publications, was a teaching assistant for the biology department, and I was the student manager for the Men's Division I basketball team. I also enrolled in the only two photography classes that were offered and participated in an independent study exploring photomicrography.

After graduation I had a myriad of industry-related jobs including managing a film processing lab and later becoming a studio assistant, all the while trying to find employment as a medical photographer. I interviewed so many times trying to enter the field during a recession, when it seemed no one was hiring. In one interview, it was suggested a better pathway into the field was to attend RIT's medical photography program. I did just that and spent a summer at the pathology photo department at Johns Hopkins Hospital where I met Norman Barker.

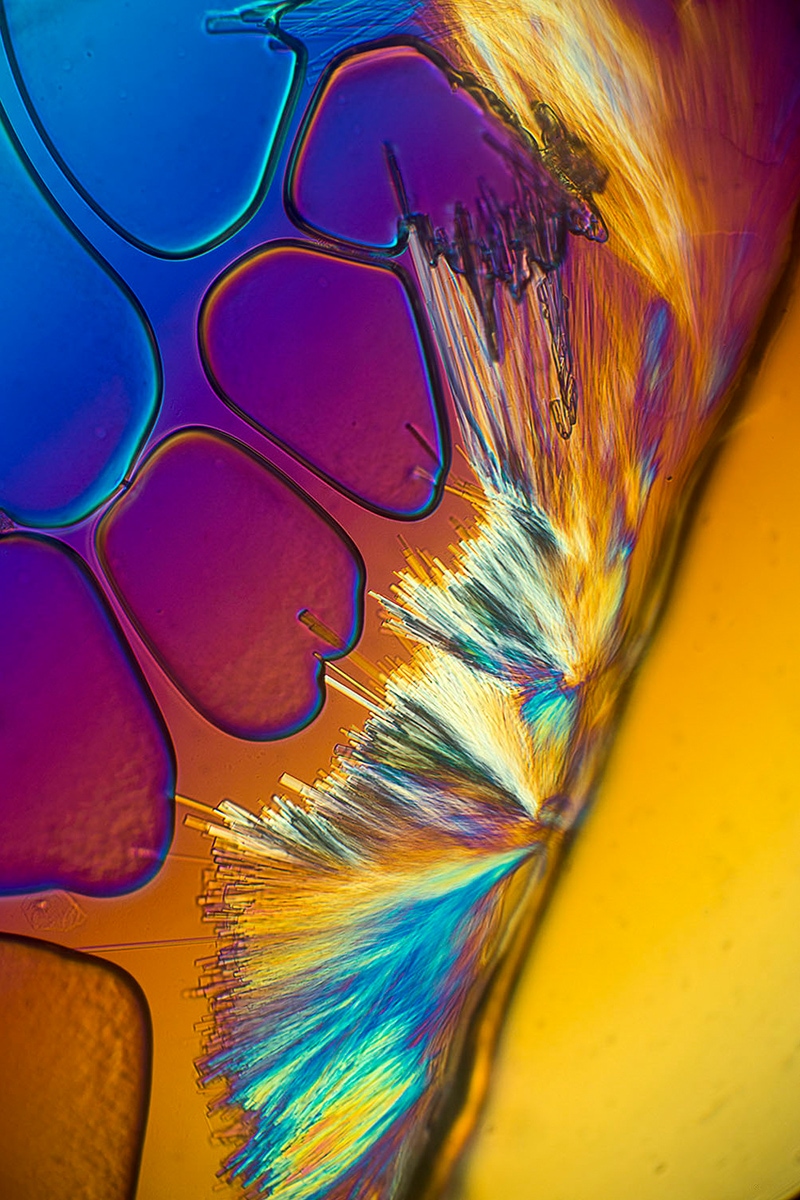

This picture features crystals that were formed from Trusopt, an ophthalmic medicine. The photomicrograph was made using polarized light and reveals the rainbow light colors of the various elements that are in the compound. The type of crystal formation is a random event but the type of crystals are unique to the compound. © Michael Peres

This picture features crystals that were formed from Trusopt, an ophthalmic medicine. The photomicrograph was made using polarized light and reveals the rainbow light colors of the various elements that are in the compound. The type of crystal formation is a random event but the type of crystals are unique to the compound. © Michael PeresShortly after graduation, I gained employment as a medical photographer in Charleston, West Virginia. There I earned my Registered Biological Photographer (RBP) certificate before leaving for Henry Ford Hospital where I became the coordinator of a student training program housed in the medical photography department. It was there that I began learning how to be a teacher. At the suggestion of Nile Root, I applied for a faculty position at RIT. I was offered a position as an instructor in the Imaging and Photographic Technology department in the spring of 1986. Becoming a faculty member of the world renowned school was both utterly terrifying and inspiring.

Describe your typical workday?

During my 35 years in academics, I have learned that when working with young adults, there is no such thing as a typical day. Their passions, curiosity, and their youth creates unique moments for them as they try new things and probe the boundaries of their comfort zones. They consistently present me with new challenges as I try to help guide them in their own pursuits.

When I started at RIT, I spent a lot of time learning how to teach. I learned quickly it is an unusual job because there are countless variables and different types of people. For example, I could never have imagined teaching light microscopy online during a pandemic with all of its unique challenges.

I feel very privileged to have been a professor for more than half of my life at arguably one of the most famous photography schools in the world. While at RIT I have experienced extraordinary changes. When I started, Kodak employed 65,000 individuals in its Rochester facilities and RIT had 151 darkrooms. Rochester's telephone area code was 716, and there was no Internet. I taught biomedical film photography classes in the College of Graphic Arts and Photography. Today, Kodak is a very small company of 3300 employees, RIT maintains 20 darkrooms, but now has computer laboratories equipped with more than 1000 high end imaging workstations. Rochester's area code was changed to 585 and I teach in the College of Art and Design. Among the most significant change is the countless digital tools that I now use to photograph the small and often invisible scientific world.

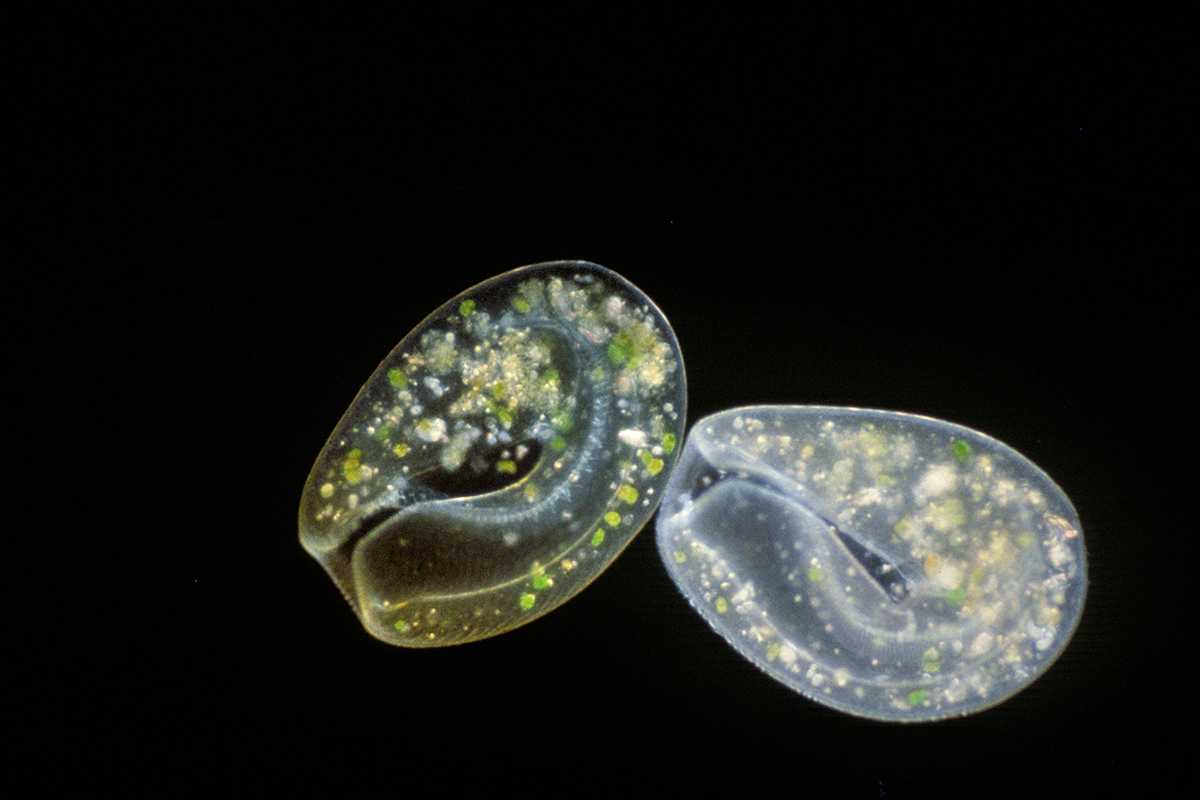

I photographed live Bursaria truncatella using darkfield microscopy. Bursaria are ciliated freshwater organisms and live all over the world. They feed principally on paramecium. I used a 10x objective and an electronic flash to stop motion. © Michael Peres

I photographed live Bursaria truncatella using darkfield microscopy. Bursaria are ciliated freshwater organisms and live all over the world. They feed principally on paramecium. I used a 10x objective and an electronic flash to stop motion. © Michael PeresAt the core of every day, I am helping students discover who they are, by showing them how to learn, and most importantly holding them accountable for their actions and my expectations of their professionalism. In this role, I am a photo educator, a confidante, a friend, a critic, a life coach, a career advisor and most importantly, a listener and role model. It is a big responsibility.

What is most rewarding about your work?

There are many things about what I do that I truly love. Watching young people become outstanding citizens and successful adults is up at the top of that list. As a result of technology and social media, I have been able to stay engaged with many of my former students, and I get to see first-hand what they have done after RIT. Some are physicians, science photographers, business owners, teachers, professors, and leaders in their communities. I am truly astonished and proud of their many achievements.

Prior to COVID, I loved the endeavors that I created including the RIT Big Shot and the Images from Science Project. That work took me all over the world. Spanning three decades, I have taught in 15 countries and was able to establish a 20 year tenure teaching a photomicrography workshop in Sweden, where I also worked with Lennart Nilsson and Nilsson foundation.

Part of my work at RIT requires new scholarship and writing books has become something I really love to do. I have a love hate relationship with the process since it takes such a long time to create a book, but seeing the finished printed volume is incredibly rewarding. Being the editor-in-chief of the Focal Encyclopedia of Photography-Fourth Edition, a book that took 5 years from start to finish to complete, was transformative to my career.

Where do you find creative inspiration when work begins to feel routine? What motivates you to continue in your line of work?

I teach in an art college, where every day when I walk into the building I am exposed to a creative and inspiring community. I teach alongside world class artists, photojournalists, wood workers and 3D animators and many others in the College of Art and Design.

This picture was the result of making several photographs and then stitching them together. I wanted a file with more resolution than a single shot would create. The fetal cat was prepared as a histological slide for embryology studies. The sample was smaller than 1cm. © Michael Peres

This picture was the result of making several photographs and then stitching them together. I wanted a file with more resolution than a single shot would create. The fetal cat was prepared as a histological slide for embryology studies. The sample was smaller than 1cm. © Michael PeresI also remain motivated by working with curious and passionate young people. I feel obligated to give them my best when I see them work hard every day and produce such good work. Dr Richard Zakia an important mentor once shared, to be respected by your students, you have to challenge them, give them your best, and "stay in the game". I think I am just beginning to fully understand his advice.

Do you have any tips or special techniques for connecting with your subject?

Making photographs is an interpretive process for me. When I started making science photographs, my goal was to be technically excellent, but my work has evolved and now I am interested in the visual process in addition to technical excellence. I have been influenced by Lennart Nilsson, H. Lou Gibson, Alfred Blaker, and Leon LeBeau, Andrew Davidhazy and countless others. When I am creating serious work, I make a plan and prepare to photograph in a certain way. I approach each subject with an idea, but remain open minded to other pathways. In the end, being curious, being informed about the subject, and being a good observer usually will direct my approaches. Nilsson once shared, "always photograph in new ways". He was right.

Do you have special interests outside of work? Do you do photography outside of work?

I love to experiment with perennial plants in my garden. My goal when I moved into my house was to not have to mow a lawn and my garden has grown significantly overtime. I also love to spend time with my family and my dogs, just being outside, taking walks, and talking. I have learned that taking a moment for self-reflection can be infinitely therapeutic.

My personal photography is accomplished mostly using my smartphone on most days. During daily walks, I make snapshots of everyday things. The world is full of things to be photographed and on occasion, I take pictures of snowflakes during Rochester's long and snowy winters.

This snowflake was photographed January 5, 2016. It was 21F. The crystal was approximately 1mm. I photograph snowflakes using a homemade photomacroscope equipped with a 25mm Zeiss Luminar lens and a bifurcated fiber optic illuminator. © Michael Peres

Do you have any advice for photographers/illustrators interested in a career in biomedical/life sciences photography?

Never stop trying to do what you love. It can be a slow and winding path to get where you want, but be persistent and follow your passion. Grow a network and meet new people. They can be the keys to success. Dare to think differently. Photographing and working in science can be a challenging place but it will never be dull. This is a small field so be patient. Good things can happen but not overnight.

Additionally please include any awards you have received or other items of interest.

- BCA Louis Schmidt Award

- RIT Eisenhart Outstanding Teaching Award

- RIT Gitner Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Graphic Arts

- Nikon Small World 9th Award, Images of Distinction

- Olympus Bioscapes Image of Distinction