A Primer for Photographing Snowflakes

Michael Peres is a professor of biomedical photographic communications at Rochester Institute of Technology. He served as program chair at R.I.T. before his appointment as associate chair of the School of Photographic Arts and Sciences. Mr. Peres has enjoyed a varied photographic career. His projects include the RIT Big Shot, Images from Science and the Lennart Nilsson Award. He has served the BCA in many capacities and in 2007 he received the BCA's highest honor, the Louis Schmidt Award.

Michael Peres, RBP, FBCA

Photographing snowflakes has become a winter past time [for obvious reasons] and began at the suggestion of one of my alumna Emily Marshall, PHB ‘04. Experience is a good teacher and over time I have developed some basic methods for photographing snowflakes that uses common equipment. This article unfortunately will be limited in how much detail can be developed because of space.

Working Outside Below 32° Fahrenheit Photographing snowflakes must be accomplished at temperatures that are below freezing and is accomplished outdoors or in unheated structures. To photograph snowflakes, all equipment must also be kept below freezing. This preserves the ice crystal for as long as possible. I place snowflakes on clean microscope glass slides for ease in handling at the microscope. Pristine snowflakes have a short life cycle. When at home, I work in my garage and when at RIT, I have found a large area that is isolated from the wind and has a second floor overhang that provides effective cover. I have also found in practice that when photographing, the temperature needs to be below 30° F. When temperatures are above 30° F, crystals begin to melt too quickly for photography. Acclimating the equipment to the cold will generally take 30 minutes or more and isolation from the wind and falling snow is also very important. A garden shed or a tent might be another good space to try and work if it is large enough to accommodate a small table

Photographing snowflakes must be accomplished at temperatures that are below freezing and is accomplished outdoors or in unheated structures. To photograph snowflakes, all equipment must also be kept below freezing. This preserves the ice crystal for as long as possible. I place snowflakes on clean microscope glass slides for ease in handling at the microscope. Pristine snowflakes have a short life cycle. When at home, I work in my garage and when at RIT, I have found a large area that is isolated from the wind and has a second floor overhang that provides effective cover. I have also found in practice that when photographing, the temperature needs to be below 30° F. When temperatures are above 30° F, crystals begin to melt too quickly for photography. Acclimating the equipment to the cold will generally take 30 minutes or more and isolation from the wind and falling snow is also very important. A garden shed or a tent might be another good space to try and work if it is large enough to accommodate a small table

Catching and Transporting the Flakes

The best way to catch and identify good snowflakes for photography is to use a piece of black velvet. I place the velvet in an 8 x 10 developing tray but truly anything that is stiff like cardboard will work for this purpose. Black velvet is ideal because it allows for easy identification of the clear flakes but also provides the easy lifting of flakes using a sowing needle taped to a pencil. Using a needle, you carefully pick up the very small delicate ice crystal and transfer it to the 1” x 3” glass slide. Efficiency is important. By the way, do not breathe heavily onto the slide once the snowflake has been transferred because you may accidentally blow it away or worse yet melt it.

Achieving Magnification Snowflakes come in many sizes and I find that working in the 4‑8X magnification range is good for photographing most of them. Achieving this magnification can be accomplished using many types of equipment. A lens that I personally have not used but would like to try is the Canon Macro Photo MP-E 65mm f/2.8 lens. This lens can achieve a 1‑5X magnification and couple directly to the Canon camera without any other accessories. Another method to achieve magnification is to use a simple microscope. This would be a standard medium focal length macro lens attached to a bellows or to an extension tube(s). A 60mm macro lens would require approximately 8 inches of bellows (separation) from the sensor to produce this magnification. A shorter focal lens would provide higher magnifications. A stereo microscope will also work and so will a compound microscope. Most compound microscopes come with illuminators and should be equipped with low magnification objectives such as 2x and 4x to photograph snowflakes. Coupled with the secondary magnifier of a microscope, the magnification will be (sometimes) too high for photographing an entire flake.

Snowflakes come in many sizes and I find that working in the 4‑8X magnification range is good for photographing most of them. Achieving this magnification can be accomplished using many types of equipment. A lens that I personally have not used but would like to try is the Canon Macro Photo MP-E 65mm f/2.8 lens. This lens can achieve a 1‑5X magnification and couple directly to the Canon camera without any other accessories. Another method to achieve magnification is to use a simple microscope. This would be a standard medium focal length macro lens attached to a bellows or to an extension tube(s). A 60mm macro lens would require approximately 8 inches of bellows (separation) from the sensor to produce this magnification. A shorter focal lens would provide higher magnifications. A stereo microscope will also work and so will a compound microscope. Most compound microscopes come with illuminators and should be equipped with low magnification objectives such as 2x and 4x to photograph snowflakes. Coupled with the secondary magnifier of a microscope, the magnification will be (sometimes) too high for photographing an entire flake.

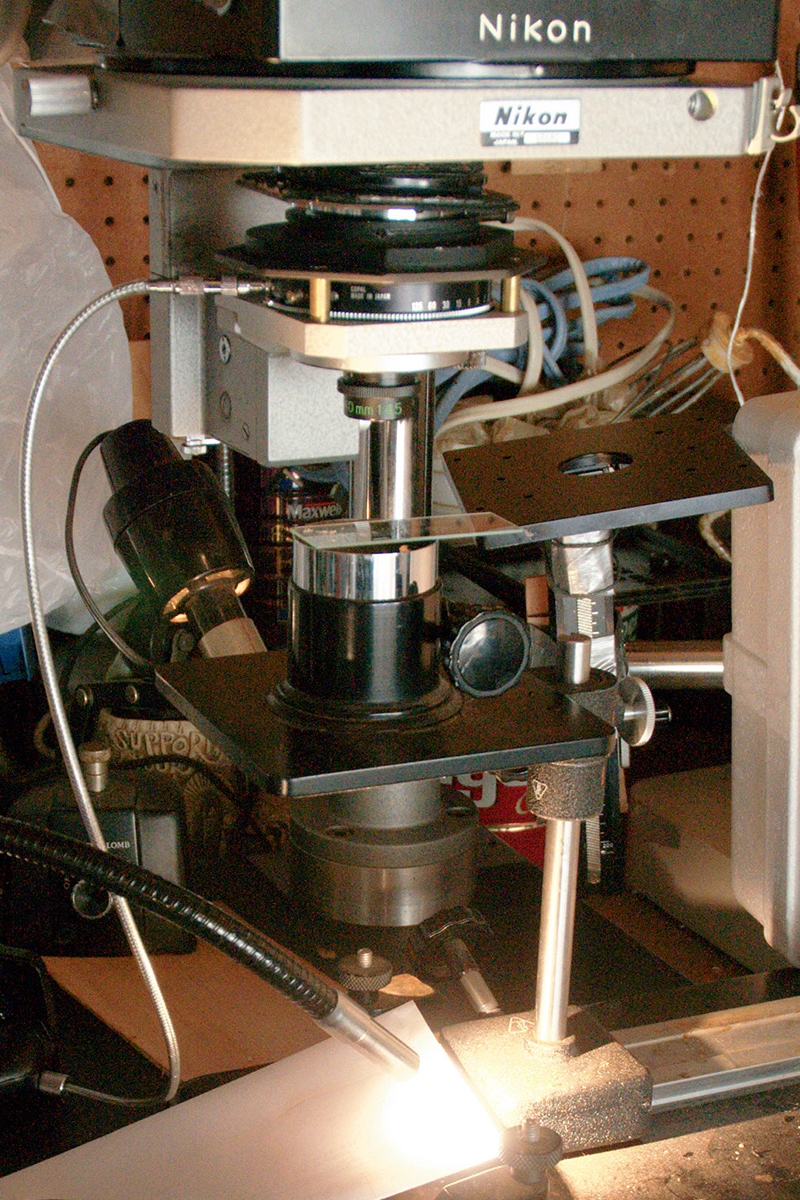

Attaching a Camera to a Microscope

Coupling a DSLR camera to a microscope can be difficult or easy depending on many things. If you use a camera with an attached lens, such as a smartphone, place the camera’s lens at the eye point produced by the photo ocular. When this is accomplished, the camera’s lens will relay the image from the microscope effectively to the sensor. I usually suggest setting the camera to its widest focal length setting possible when using this technique. Hand holding the camera will be very difficult but not impossible. The alignment of camera is very critical. Most of the time, I use a tabletop copy stand and I suspend the [compact digital] camera over the photo eyepiece. If you do not have vertical stand, you can use a tripod and locate the microscope on the ground. I have also cannibalized an old enlarger by removing the enlarging head and replacing it with a wooden camera plate. The plate has a ¼-20 bolt/wing nut for use as a camera attachment. This stand has worked quite well when considering its cost. If you are fortunate enough to be using a photomicroscope, the camera system may already be integrated.

If you are using a DSLR camera, I suggest you take off the lens and suspend the camera over the eye point using the same method described above except the camera will be at a different location. The distance can be determined by the locating the distance where the microscope’s image is large enough to cover the sensor. By using black construction paper or a similar rigid black material, I suggest you create a tube to act as a light baffle around the microscope's photo tube. This baffle should be long enough to reach the camera body but not enter the camera. This baffle will block extraneous light from being imaged. Care should be taken with either camera type to ensure the camera’s sensor is perpendicular to the optical axis. If the camera/sensor is not oriented properly, focus will be lost across the field of view.

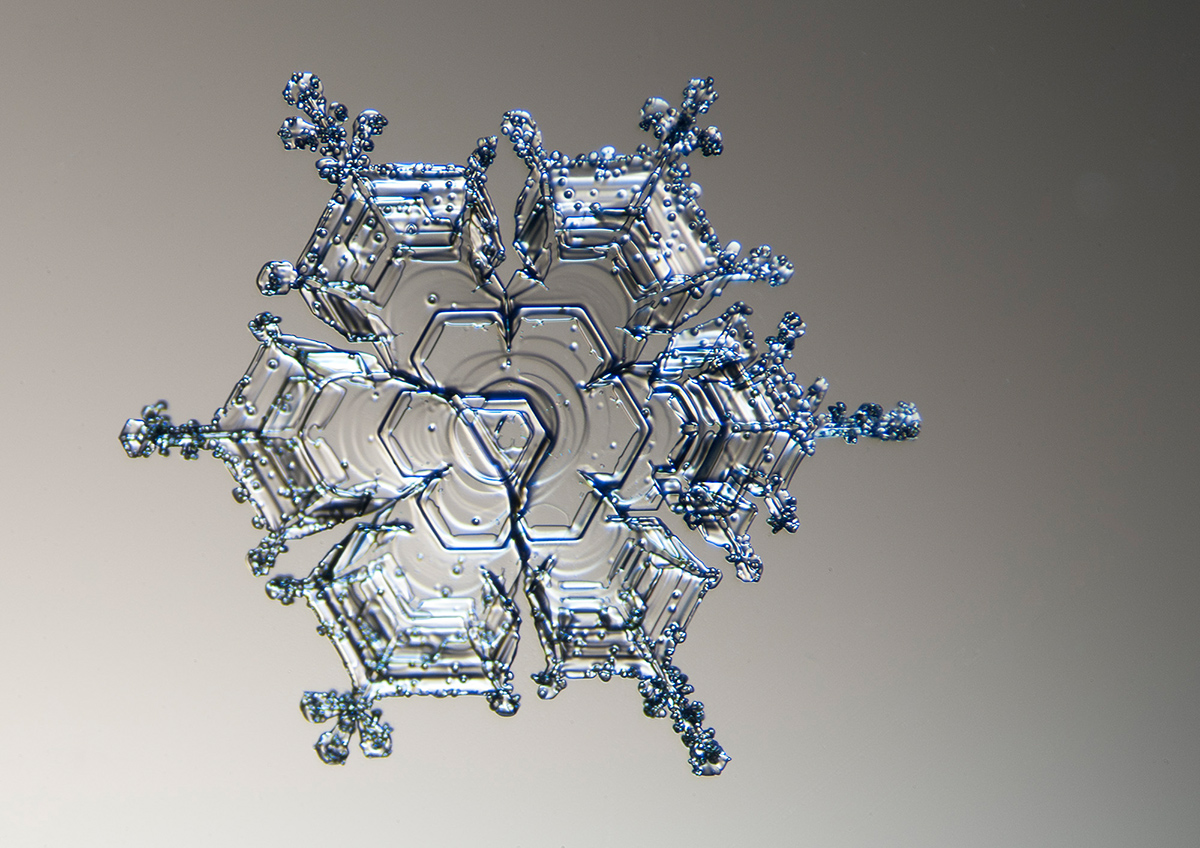

Illumination Light is a key ingredient for interesting photographs of all types and most often I use a fiber optic illuminator for snowflakes. This light is used to supplement the microscope’s built-in illuminator and will lead to images with interesting internal reflections. The snowflake’s structure is much like a diamond with its many facets. Producing light that creates internal reflections and refracts in the flake’s numerous facets is my ultimate goal. I have used color gels, color backgrounds as well as monochromatic strategies. One of the things I enjoy the most is learning how to light the flakes. Before I forget, be sure to trigger the camera using the self-timer. When you are cold, you will absolutely introduce shake into the image.

Light is a key ingredient for interesting photographs of all types and most often I use a fiber optic illuminator for snowflakes. This light is used to supplement the microscope’s built-in illuminator and will lead to images with interesting internal reflections. The snowflake’s structure is much like a diamond with its many facets. Producing light that creates internal reflections and refracts in the flake’s numerous facets is my ultimate goal. I have used color gels, color backgrounds as well as monochromatic strategies. One of the things I enjoy the most is learning how to light the flakes. Before I forget, be sure to trigger the camera using the self-timer. When you are cold, you will absolutely introduce shake into the image.