Andrew Robin Williams, BSc, MPhil, PhD, FBCA

Andrew Robin Williams, BSc, MPhil, PhD, FBCA is honored with Emeritus Membership for over his 40 years of service and contributions in the field of biocommunications.

Dr. Robin Williams is an Accredited Senior Scientific Imaging Scientist, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine, the Royal Photographic Society, the Royal Microscopical Society, the British Institute of Professional Photography, the Biological Communications Association, the Institute of Medical Illustrators, and the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators. He is an Honorary Fellow of the International Academy for Television Arts and Sciences, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie (Germany) and the Foreningen fur Medicinsk och Teknisk Fotografi (Sweden). He has been awarded the Louis Schmidt Award of the BCA, The Chairman’s Award of the Royal Photographic Society, the British Medical Journal Award, The Gold Medal of the Royal Microscopical Society, The Norman Harrison Medal from the Institute of Medical Illustrators, the President’s award from the British Institute of Professional Photography, The Lancet Award, and the Williamson Research Award. Dr Williams is unique in having been awarded the Combined Royal College’s Medal twice – this is awarded jointly by the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal College of Surgeons and the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and is recognized as the highest award in the field of medical imaging. He has authored over 70 scientific papers and books and has given over 400 presentations. His work has been widely exhibited, is in many public and private collections, and has been published in for example, Time Life, National Geographic, The Observer and New Scientist.

Get to know Emeritus Member Dr. Robin Williams

What inspired you to pick up a camera?

From the earliest age I can remember I had a camera in my hand. Photography has been a consistent theme in my life – not always my aspiration, not always my main source of income – but never far from my heart. I am at one when making images. My Father introduced me to the mesmerizing sight of a print coming to life in the tray of developer. By the age of eight I was ‘in love’ and my ‘Grande Passion’ for photography was never to leave me.

What drew you to your chosen field of photography?

My parents and teachers had become comfortable with the idea of me being a professional photographer on leaving school so Imagine the shock and disbelief when I boldly announced that I wanted to be a doctor! Whilst studying in my final years at school I found a second grande passion – the human body. A chance encounter set my agenda and shaped my life for the next fifteen years – I met a professional medical photographer! I discovered a way to combine my passions for human biology and photography – I would become a medical photographer.

Where did you get your training?

I went to do a degree in scientific and medical photography; London boasted one of only three such courses anywhere in the world. Photographic College turned out to be a huge disappointment – I already knew most of the course content. Thankfully University does not require attendance except for examinations and I was encouraged and supported to spend my time away from campus and out in the industry. During the first year I worked at GEC Marconi – which challenged me photographically and engaged me for the first time in a whole range of highly specialized imaging techniques and equipment. For the latter two years I worked at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, I adored Cambridge - a heady intellectual and emotional mix. I was elated to be in one of the finest medical institutions in the country studying under one of the great masters of medical photography – Leonard Beard. I made friendships that would last a lifetime and I made images that would create a future career. I learned how difficult it was to produce photographs of people who were sick, and in pain, to such a high standard that they could be repeated exactly over months, or years. I learned how photography (and hospital) can strip patients of their dignity. I learned how to take photographs in surgery – the ‘decisive moment’ that could never be repeated. The people around me taught me more than a craft and a profession, they inspired me. I graduated with Honours in both Scientific and Medical Photography. Having said all that, I always got my real training ‘on-the-job’ working all my life with talented and generous people (many of whom were BCA members).

What positions did you hold during your working life? Are there any memories that stand out?

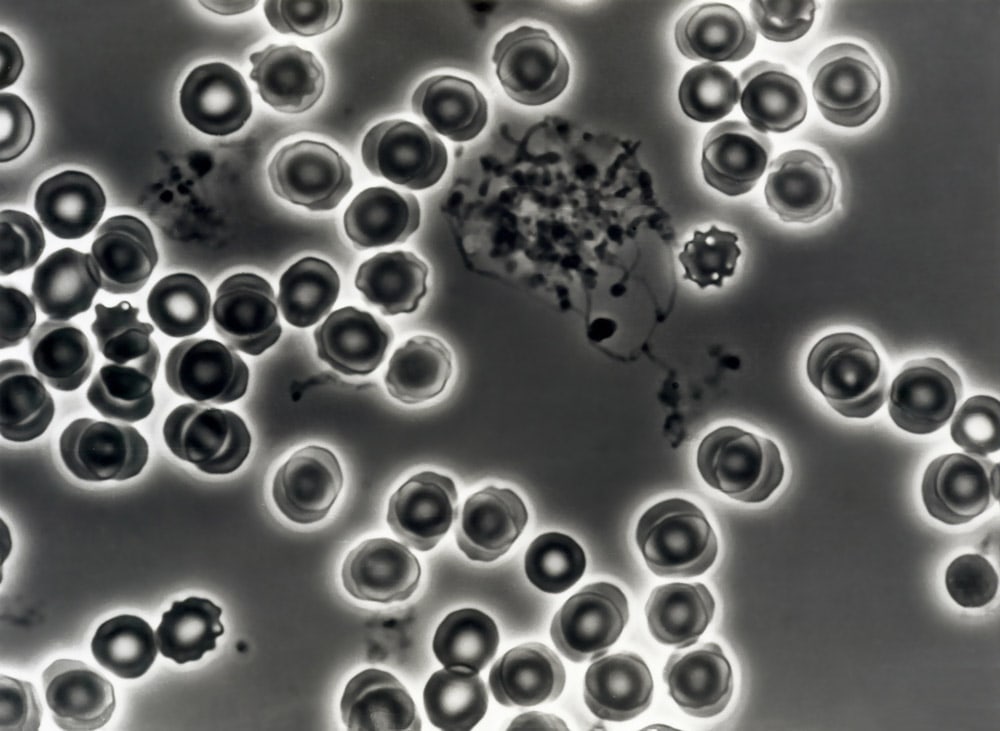

Phase contrast microscopy of live human blood passing through a cardiac hypothermia pump showing crenellation and fibrin formation.

On graduation in 1974 I went to work as a medical photographer at Westminster Hospital in Central London. The department at Westminster was a powerhouse filled with talent. I was engaged daily in imaging to support clinical assessment, research and teaching. I loved my work – during my years there I photographed approximately 12,500 patients, 1,500 surgical operations, 1,000 autopsies and 2,000 pathological specimens. People are amazed today to learn that most of our work then was done on large format 4x5 cameras with sheet film and sometimes plates! For colour transparencies Kodachrome 25 was the only option. I cannot tell you how exciting it was to work with such talented people, or how interesting the photography was.

I have so many memories of working at Westminster including working with a brilliant young cardiologist, where I invented a method for photographing super cooled blood passing through a cardiac hypothermia pump. The technique resulted in the first ever recognition of erythrocyte crenulation and subsequently dramatically improved techniques of open-heart surgery.

I also developed an innovative range of photographic methods for the measurement of three-dimensional shape, volume and surface area in vivo – contour maps of patients. My techniques were adopted by Hospitals in the UK and as far afield as USA, Canada, Japan, South Africa and Australia, and used to improve outcomes for children undergoing facial reconstruction surgery, to improve techniques for managing burns, to improve the treatment of thousands of young patients with spinal deformities such as scoliosis, and to monitor treatment in cancer therapy. Another project required me to work in the Crypt of St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street – which had a collection of layered skeletons going back to Roman times. My anatomy colleague had a theory that the sacro-illiac joint was compromised by early pregnancy and so wanted to measure bones of young women dating back through the Centuries. I was required to photograph hundreds of pelvises in situ in the Crypt in such a way that distortion-free, detailed and accurate measurements could be made from the photographs. I had to invent a system that would record the bones as if the photographs had been taken from infinity – a telecentric system.

Demonstrating the world’s first, fibre-optic based, two-way television communication system to Princess Anne (Chancellor of the University of London). The system connected eight teaching hospitals across London.

In 1979, at the age of 27, I became Director of Medical Illustration and Teaching Services at the new Charing Cross Hospital in West London – the largest department in Europe – I would spend the next fourteen years operating on a much broader canvas and an international stage. Five years after starting as the Director at Charing Cross I implemented the merger of the Westminster and Charing Cross departments to create one of the most advanced media and communications supports for teaching and research in medicine anywhere in the world. Seven years on I would initiate the successful privatization of the service. I led many significant initiatives in this role, for example, by the early 1980’s we had a fully connected Apple Macintosh Network for the production of desk-top publishing and computer graphics (the first such application in Britain). Probably the most exciting project of all in this role was the conceptualisation, design and installation, of the world’s first, totally interactive cable television network based on fibre-optic communications technology. This system enabled high quality, full motion, two-way television with associated clinical monitoring to be broadcast between eight teaching locations across London. Around the same time we began some of the first experiments in high definition colour television in collaboration with Sony. I also led the early experimentation with electronic imaging systems in medicine using both the Sony Mavica and the Canon RC-701. It’s difficult to believe that we have come so far – these early systems had a resolution of just one megapixel and stored a few images on small floppy disks! In 1990 in partnership with Prof Peter Venesis, I established the National Centre for Facial Recognition and Identification. This involved designing and installing a system for accurate three-dimensional measurement of faces and skulls. The aims were to build a statistically valid database of facial shape and to develop tools by which facial shape could be predicted from skeletal remains. This was the start of a long engagement with forensic science and images in the courtroom.

In 1992 was appointed as a full professor and Head of the photography department at RMIT University in Melbourne Australia. I spent over twelve years at the University in four roles. The Headship of the Department of Photography offered me the opportunity of re-creating within the very core academic disciplines themselves the convergence of media and communications services that I had achieved in units supporting academia in London. Within two years I transformed the department of photography by motivating staff, engaging industry, creating new and exciting products, and bringing together a whole range of disciplines by merger, acquisition and new growth. This resulted in the creation of the new ‘Department of Visual Communication’, which I then managed. The establishment of the Department of Visual Communication marked the beginning of a key international leadership role for the University and for me personally. Digital convergence was changing the world of work and leisure – creative content was King – fulfilling Marshall McCluhan’s prediction. I led the development of the new field of interactive multimedia both within the Department and across the University as a whole. I established the Apple Creative Media Centre and the International New Media Centre. I conceived and then established the Interactive Information Institute to conduct commercial, collaborative research and innovation with partners across the globe. Our work became the centre of international attention and I personally continued to give papers at conferences, write for journals and sit on committees at the highest level. I was a trusted advisor to government leaders, including the Prime Minister and Premier, at both State and Federal level. I was also engaged internationally in providing expert advice. UNESCO invited me to accept the role Professor of Communications for the Asia Pacific Region in 1997 and so I undertook this role in parallel with my full-time role at RMIT. This involved skills and knowledge transfer to developing nations.

In 1999 I became the Executive Dean of the Faculty of Art, Design and Communications at RMIT University. This position involved the direction, management and academic leadership of one of the largest and most comprehensive faculties of its kind in the world. The Faculty had 10,000 students studying over 100 undergraduate and post-graduate courses organized within five Schools and several research centres. The Faculty operated on three Australian campuses and had extensive international engagement. I was responsible for a total of 600 academic, technical and administrative staff. The Faculty had an annual budget of $80M, 40% of which was raised from sources outside of government grants. I spent the final nine years of my academic life in the President’s Offices of two Australian Universities working as VP international Education, VP Advancement and VP External Engagement.

Did you have a mentor?

My father – his influence went well beyond introducing me to photography. In my early years my father had been a lighting director in the theatre and some of my earliest memories were of Dad creating illusions with light. It was as a child that I started to learn about shade and light, chrominance and luminance and began instinctively to understand how to create emotional responses through lighting. I learned to respect and value light. But my real mentor was the ‘Godfather’ of Medical Photography – Dr Peter Hansell – Founding Director of Medical Photography at Westminster Medical School in London. Dr Peter Hansell was an ophthalmologist who along with a few colleagues had created the profession of medical photography after the Second World War. Peter was a ‘King Maker’ – his past staff had gone on to successfully direct units all over the world. Peter Hansell nurtured my entire career including encouraging me to take a Masters degree and then a Doctorate in Medicine. Peter died at the age of 80 in 2002. He was generous with his time and talents and nurtured generations of medical photographers, myself included. I miss his friendship and wisdom.

When did you join BPA/BCA and what positions, awards or certifications did you hold?

With Roger Loveland, Photomicrographer Extraordinaire, teaching at the 1993 Rochester Workshop.

I joined the BPA in the 1970’s and gained my Fellowship in 1982. I was a Member of the Board of Governors and a Director from 1986 to 1989. I was the Founding Chair of the Endowment Fund for Education and could be seen regularly on the stage running the annual auction for the fund. I was a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Biological Photography, a member of the Fellowship Committee and the Louis Schmidt Committee. For many years I taught on the BPA/Kodak Rochester Workshop and regularly presented papers and workshops at Annual meetings. My first presentation at a BPA meeting in Toronto won Best Paper Award and this was followed by many other such awards – Rochester, St Louis, Denver, Dallas and Phoenix to name a few. I have received several Lou Gibson Awards for Best published paper in the Journal and have regularly exhibited in the professional exhibition, with many first-place awards. I was honored with the Louis Schmidt Award in 1993.

How did BPA/BCA influence your career?

Actively being a part of a professional association, like the BCA, where you share information freely is a vital part of your on-going professional development. Being able to compare your work with your peers, learn from colleagues and be inspired by industry leaders is invaluable in your career progression. But most of all, you make good friends – some of which last a lifetime.

The Golden Lotus at the moment of fertilization – winning entry of the International Garden Photographer of the Year competition in 2020."

Please share with us what your retirement has been like.

Towards the end of my career I got further and further away from my photography and retirement has enabled me to spend much more time enjoying my passion for photography. Retirement has also enabled me to spent quality time with my true love – my wife Gigi (also a Louis Schmidt recipient and Emeritus Member) – together we travel the world pursuing our interest in landscape photography. Over recent years I have established myself as an internationally recognized landscape and fine art photographer with over 50 National and International prizes and awards, including, in 2020, International Garden Photographer of the Year (which had over 20,000 entries from over 50 countries). I still get excited when we go out on a shoot – I have yet to take my best photograph!

Lastly, what advice or wisdom would you impart to anyone wanting to pursue a career in any field of photography today?

Take the time and effort to study photography on a graduate program – you can’t learn how to be a competent professional from the internet. Be passionate about your work and strive for excellence; if you do that the opportunities to do interesting work and the associated recognition will follow. If you’re not passionate about photography, don’t do it – life’s too short to do something you don’t love.

Of necessity this is the briefest outline of my photographic life. If anyone has the interest and inclination they can find my full curriculum vitae and autobiography on our website at: https://www.robinwilliamsphotography.com/about

Teaching a workshop in Sweden. I was a champion of standardization in clinical photography and taught workshops on the subject all over the world for many years.