Congenital Pectus Excavatum pre- and post-operative

© Marie Jones, BSc, FIMI, PgCHE, FHEA, AHCS, fCMgr

Congenital Pectus Excavatum pre- and post-operative received an Award of Excellence in the Image Series category in BioImages 2022.

Pectus excavatum is a congenital condition, affecting 1:1000 children with a 4:1 ratio of boys to girls and may be associated with another syndrome such as Marfan’s Syndrome. In pectus excavatum, the sternum is ‘sunken’; therefore, the ribcage may interfere with the normal function of the heart and lungs, causing problems with expiration and the ability to exercise. The patient may also be self-conscious due to the appearance of the chest.

Reason for the image creation, purpose, and audience

In the U.K. Cardiothoracic surgery is not routinely funded through the NHS, therefore the patient needed to apply for funding for NHS surgery. Pre-operative photographs (left) were used to support this patient’s case for funding the surgery. The images were considered together with additional clinical evidence from the patient’s GP and health professionals involved in his healthcare. The funding for the surgery was approved, and the photographs were available as part of the patient’s healthcare record to inform the surgeon and multidisciplinary team.

The patient was very interested to view his medical photographs, he considered them ‘striking’ and stated that he was ‘glad to have the photographs to remember what it was like before surgery’. The patient recovered well from the surgery and presented for photography four weeks post-operatively. Comparing the pre-op (left) and post-op (right) images enabled the patient to see the vast improvement in the appearance of his clinical condition. Patients are able to request copies of their medical photographs and, as with this patient, often find it helpful to visualise their clinical progress.

The patient also gave his permission for the photographs to be used for teaching, publication and research purposes.

Equipment and Specifications

Nikon D500 APS-C DSLR (DX); Nikon 60 mm f/2.8 D AF Micro-NIKKOR macro lens. Focal length: 60 mm (DX), equivalent to 90 mm FX.

Exposure: Pre-op: ISO 200; f/25; 1/125th/sec f/25; Post-op: ISO 200; 1/160th/sec f/22

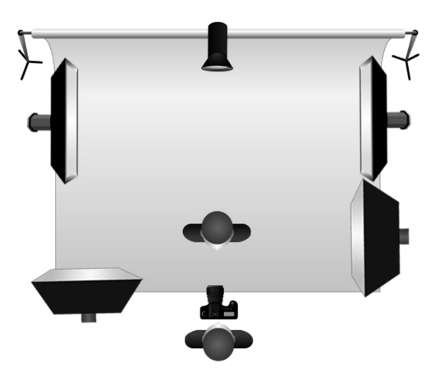

Studio lighting: Key and fill lights - x2 Bowens XMT 500 flash heads (battery powered); Rim lights - x2 Bowens 500 flash heads.

Lighting technique: Studio flash ‘cross’ lighting.

Method

I commonly use the cross-lighting technique. It is a simple but subjective method of lighting used to demonstrate texture, depth and form by accentuating the shadows in the relief areas of the image, hence, giving a more ‘3D’ effect than would normally be viewed under ‘flat’, even lighting.

Two front lights are used: one as key light and the other as fill light, together with two lights behind the subject as rim lights to ‘separate’ the subject from the background.

Challenges

The challenge when demonstrating the pectus excavatum clinical presentation in this image was to ensure that the highlights and shadows balance in order to retain detail in both. The histogram used both in camera whilst photographing and referred to in post-processing gives a useful indication as to the shadow and highlight values. I always aim to get the exposure, focus, positioning of the patient and framing correct at the time of photography to ensure integrity of the image and less digital manipulation when processing. Exposure is particularly important to ensure accurate skin colour. I think of the photography process as if I were shooting on transparency film for the final image to be as it appears in-camera.

The medical photography studio is fairly small and is equipped with battery operated flash heads mounted on wheeled flash stands - I use these as the key and fill lights. This results in greater speed and flexibility due to not having to avoid mains cables; this is also good for patient and photographer safety as would be the case when using ceiling mounted lighting. This set-up enables me to achieve high quality, accurate images.

Summary

Being able to achieve high quality, effective clinical images that benefit the patient, health professionals and research into a rare clinical condition is an extremely satisfying outcome. This ability is the difference between just an amateur snapshot and a professional quality image, and in this case, gained the approval for funding the surgery that had previously been denied for this patient.

With today’s reliance on imaging to inform clinical decisions and enable patients to visualize their own clinical condition, the medical photographer is a valuable member of the multidisciplinary team.

Biography

I have been working as a medical photographer since 1989, starting as a trainee and now manager of the medical photography service. Over the years I have moved jobs in order to gain more experience and I have gained academic and vocational qualifications along the way – ‘learning on the job’ can be tough but also very satisfying and rewarding. Clinical photography combines my interests in medicine, science, art and interaction with patients and health professionals and I would highly recommend it to anyone with interests in these areas.

Membership of BCA

Since joining BCA, I have enjoyed being part of a welcoming and friendly medical, scientific and artistic community, this has enabled me to gain knowledge and advice from my peers, and share my own knowledge, skills and experience and passion for these interests.

BioImages

I continually aim to improve the images I produce. Entering BioImages gives me the opportunity to review my clinical and non-clinical images. As well as clinical subjects, I also enjoy photographing wildlife and nature subjects, ranging from vast landscapes to infinitely small macro subjects. BioImages, means that I critique my own work and ask for my peers’ reviews when considering images for inclusion in this annual competition.